Chesterfield Reef

Cruisers in the tropics of the South Pacific have to make a critical decision as cyclone season approaches in November: find an anchorage that qualifies as a hurricane hole for the season? Head south to New Zealand? Follow the sunset west to Australia?

Dominic and I had been in Vanuatu, swimming in waterfalls, swinging from banyan trees into freshwater springs, eating freshly caught lobster and mahimahi everyday, and wishing away the realities of the calendar, when we were forced to address this question as the days in October 2016 dwindled.

Having spent the previous summer in New Zealand and not in the mood to gamble with cyclones, we started planning a 1,000 nautical mile passage from Luganville, Vanuatu to Bundaberg, Australia.

We had been monitoring the weather for a month but didn't see any good windows that would allow us to comfortably sail the full distance in one hop. Friends that had made the passage a few weeks earlier told us about a little-known sliver of paradise called Chesterfield Reef that lies just beyond the half way point of our intended trajectory through the Coral Sea.

We started researching, finding that if Chesterfield is defined by anything, its isolation: 560 nautical miles southwest of Luganville, 440 nautical miles northeast from Bundaburg, the reef hovers 470 nautical miles northwest of Noumea, New Caledonia, from where it has been governed as a French territory since 1876.

Remote, yes, but a perfect stopover for us. And when we saw our friend's photos of turtles on the beach and seabirds flocking around their dinghy, we were really sold. So when November 1 rolled around, we started filling the larder, de-molding our lifejackets, and making ready for a passage to Chesterfield Reef.

Checking out of Vanuatu brought the usual throng of emotions: the sadness of saying goodbye, the thrill of new adventure, the fish-in-the-tummy anxiety of whatever unknowns the ocean held hidden in her waves.

On November 8, 2016, we raised the main, unfurled the jib, and enjoyed the first breeze we had felt in the cockpit for weeks as we set a westerly course from Luganville. Outside the lee of the island, a brisk 17 knot wind blew in behind us, and the seas swelled to 1.5 meters.

The sunset brought a star-studded night with winds that fluked and dipped to 10 knots, causing early morning sail furling and engine starting. But by morning they steadied, and we were sailing under a full mainsail and jib.

After 48 hours, we rounded New Caledonia's northern reefs; once in her lee, the seas were pancake flat. We had a magnificent day of sailing, the wind blowing for 12 hours longer than the forecasts called for, but we fired up the engine that night after the winds died and expected to motor the rest of the way.

We had an inkling a hundred miles out of Chesterfield Reef that we would be in for a lot of birds—three red footed boobies roosted overnight on our bow, one slept on our spreaders turning our dodger, deck, and mainsail into a modernist masterpiece of black and white smears.

One of the boobies we later spotted on shore:

As we approached the pass into Chesterfield, we started to see four-foot brown sea snakes float by our starboard side. We had a bite on our trolling line. Reeling in the catch, we noticed a gray reef shark trailing the boat. The shark made a lazy dive, disappearing into the sapphire, and our catch was gone.

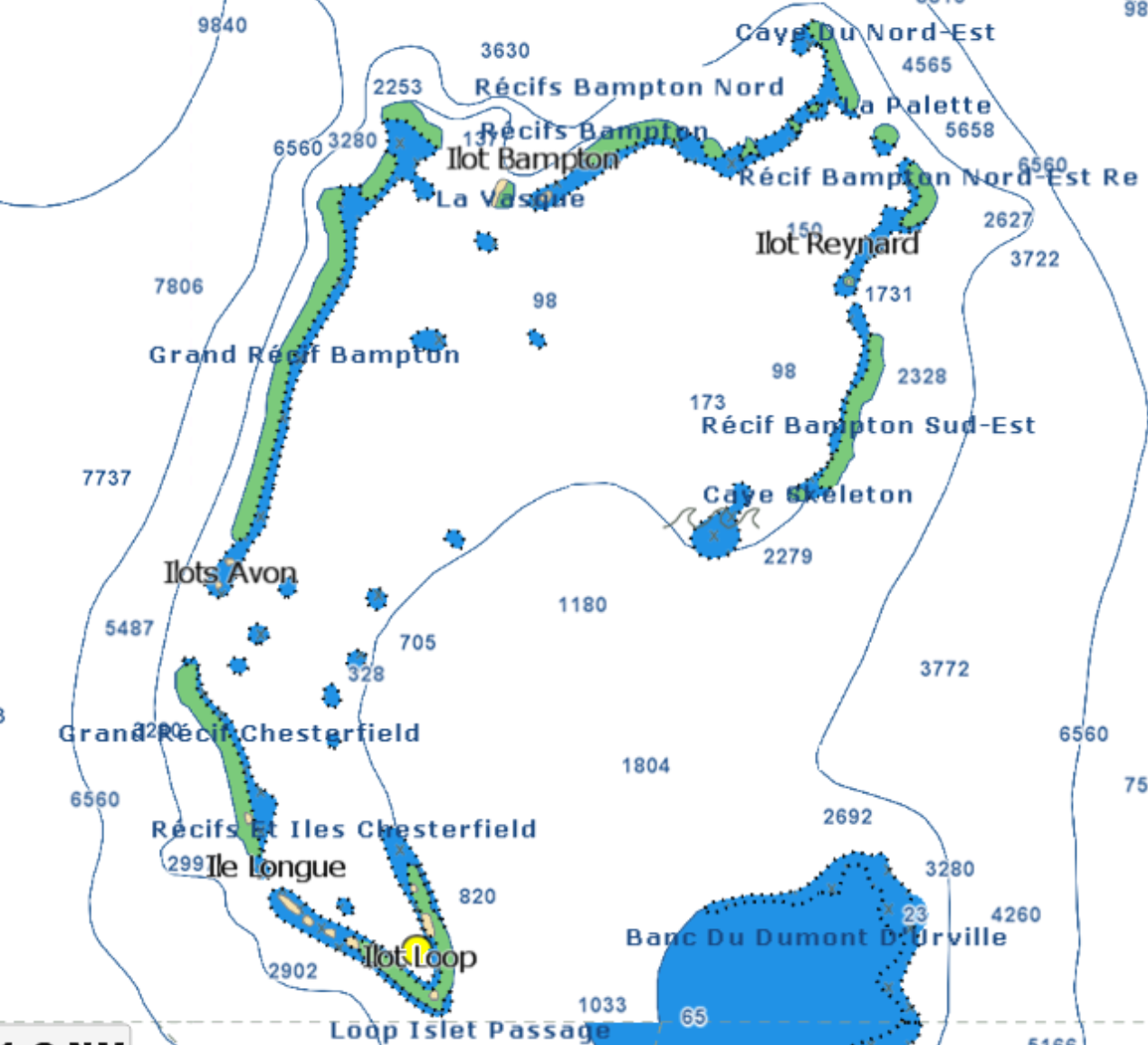

After four and half days underway, we arrived at Chesterfield Reef. The reef is shaped like a bent fishhook, with a large opening facing the east, so navigating the entrance was straightforward. The lagoon is mostly free of coral heads and navigational hazards.

The reef, as seen on our charts and Google Earth:

There are 11 motus surrounding the lagoon that form a bight along the southern end creating an anchorage protected from southerly trades. We noticed that bommies became more frequent as we approached the reef's perimeter, so I went to the bow to keep a close lookout as Dominic navigated Helios into the anchorage. In reality, this is one of the easiest anchorages we've entered in our previous 13,000 nautical miles.

The view as we approached the anchorage:

By 1230 on a sunny Saturday, November 12, our anchor was dropped, the champagne popped, and we were moments away from swimming in the glassy turquoise water surrounding the boat. With us were three other cruising yachts, two catamarans out of Australia and Breeze, a 64 foot Moody, out of Sweden.

Scoping the neighborhood from the bow:

Helios and Breeze, as seen from shore:

We quickly realized those calm, clear waters were not as benign as they looked. Breeze reported seeing a three meter a tiger shark circling her stern after cleaning a fish and tossing the remnants overboard.

But still, I couldn't resist going for a swim after such a hot sail. So while I floated, bobbed, and somersaulted in the water, Dominic wore his snorkel and mask and kept a constant shark watch.

The tiger shark population in Chesterfield is unique and well documented. The reef system provides year-round shelter to an adult male tiger shark and at least three juveniles. A 2014 study recorded adult females passing through the area as part of a three-year migratory pattern around the Coral Sea via Australia and southern New Caledonia.

We tentatively, cautiously, on high shark alert at all times did some underwater exploring of the coral near the anchorage.

Our bravery was beyond rewarded. We spent an hour swimming around a large bommie 100 meters from the boat. The water was diamond clear, and the bommie was swollen with coral, humming with fish of all sizes. Crimson and evergreen sea fans waved in the current.

Dominic brought his spear gun with him, but it was only to play defense in the unlikely event that we came in contact with aggressive wildlife. Though we usually enjoy fishing, spearing can cause nearby sharks to become curious and assertive, a situation we were hoping to avoid. Plus, areas of Chesterfield are reported to be contaminated with ciguatera, a toxin that gets magnified in the reef food chain and causes nerve damage and muscle pain in humans.

Surrounding the anchorage, there were four continuously exposed motus that provided nesting sites for thousands of birds. Masked boobies sat on eggs and raised their young on the sand; red footed boobies built nests in the bush-like trees; black noddies roosted on low lying shrubs, raising their young in the shade below; two juvenile frigate birds haunted the skies, resting on whatever branches they could find.

A juvenile frigate bird circling the motu:

An adult human circling the motu:

The birds have been integral in forming what little exists of Chesterfield's landscape. The islets are built of coarse, coral sand, sand stone, and abundant layers of guano.

A booby tending her eggs:

A booby and her just-hatched babe:

A pair of masked boobies and their adolescent chick:

Similar to the sanctuary Chesterfield Reef provides for tiger sharks, the nesting sites on land provide one of the last pristine habitats for scientists to study seabird behavior. As of 2010, Chesterfield and her neighbor, Bellona, housed upwards of 300 mating pairs of masked boobies, 4,000 pairs of brown boobies, 7,000 pairs of red footed boobies, 1,800 pairs of frigate birds, and 30,000 pairs of black noddies.

A noddy and her chick:

On our third day at the reef, the winds backed to the northerly quarter, kicking up chop in the lagoon. We were in for a bumpy night no matter our location, so we moved to the western side of the reef to explore a second anchorage and be nearer to the southwesterly pass for our exit the following day.

We dove the reef system between Helios and shore, finding more thriving coral and schools of emperor fish. The excitement came when a four-foot turtle emerged out of the blue, swimming directly at us. He was inquisitive and friendly, coming within a few feet of us and circling back to check us out three times. It was spectacular to encounter wildlife so untouched by humans that their response to us was curiosity instead of fear.

Our favorite turtle photo:

But not all the creatures in the lagoon were so lucky—we spotted two illegal fishing boats while we were in Chesterfield, a large 'mother ship' that lingered outside the reef and a smaller satellite ship that worked inside the lagoon. We saw the the vessel inside the lagoon up close, and the crew appeared to be diving for sea cucumber and using nets to hoist their catch out of the water.

Chesterfield Reef and her surrounding waters are part of New Caledonia's Exclusive Economic Zone, meaning foreign vessels without permission are forbidden from fishing in the region. Similarly, New Caledonia has recently designated the waters within her EEZ as a natural park, limiting domestic fishing and hoping to eventually extend protection as far as Australia's aquatic preserve to the west.

Nevertheless, it isn't uncommon to find illegal fishing boats from the north working in the area. Within the Coral Sea in recent years, vessels from Vietnam, China, Taiwan, and Papua New Guinea have been caught harvesting large amounts of sea cucumbers, tuna, shark, and smaller quantities of turtle meat and reef fish.

The dwindling tuna and shark populations are well documented and of grave concern to governments and environmental groups working in the South Pacific.

Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga have joined forces to patrol waters between their EEZ's and enforce measures limiting net and long line trolling enacted by the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission.

Nevertheless, in the last five years the Secretariat of the Pacific Community has recorded as many as 320 illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing vessels within the greater South Pacific Ocean in a one-month period.

There are few things more tragic than watching a habitat as critical and unique as Chesterfield being destroyed, especially as the area has already suffered at the hands of human economics.

As we sat at anchor in Chesterfield, one of the more beautiful, remote places on earth, we were dismayed to see such destructive activity going on around us. We wanted to put an end to it as quickly as possible.

Breeze attempted radio contact, but didn't hear any response. We passed the satellite vessel as we crossed the lagoon, taking as many close-up photographs as we could to document what we were seeing. We emailed those photographs to the New Caledonian Navy.

The vessel of ill repute:

A naval officer responded quickly, sending follow up photos and asking detailed questions about the vessels identifying marks. The Navy discouraged any direct confrontation between cruisers and the vessel as the potential for violence could escalate.

It was frustrating to have to sit back and watch the fishing take place—imagine being at a playground and watching one child bully another and being able to do nothing—but the quick and serious response from the Navy was satisfying.

We left Chesterfield on the morning of Tuesday, November 15, with squally skies and light southwesterly wind forecasted to back to the southeast by sunset.

On our second day underway, the winds built to 20 knots with two meter seas. We found a northwesterly setting current that gave us an extra two to three knots over ground toward Bundaberg. To offset the angle the water was moving, we had to turn the boat upwind and crab sideways toward our destination.

Upon arrival, we reported the illegal fishing activity and shared photographs with the Australian customs officers. They were interested in documenting the situation, but didn't seem at all surprised to hear about it.

ps. In real time, we're in Australia enjoying a fantastic day sail from Bundaberg to Frasier Island. We were so inspired and intrigued by Chesterfied Reef we wanted to learn more about what we experienced and get a chance to share more photos.